Nature’s Petrifying Secret: Tanzania’s Lake Natron is one of the most bizarre and chilling places on Earth. It’s not just a salt lake—it’s a chemical anomaly where animals are calcified after death, appearing eerily frozen in time. This natural phenomenon has both fascinated scientists and mystified locals for centuries.

Located in the remote northern part of Tanzania, near the Kenyan border, this alkaline lake has been dubbed “the lake that turns animals to stone”—a fitting, if slightly dramatic, description. But the truth is both scientific and spectacular. In this guide, we’ll unpack the full story: what makes Lake Natron so deadly, why some creatures survive there while others don’t, and what scientists, travelers, and conservationists need to know about this uniquely extreme ecosystem.

Nature’s Petrifying Secret

Lake Natron is unlike any place on Earth. Its extreme chemistry turns death into eerie preservation, yet it sustains a thriving flamingo population and rare microorganisms. A place of contradiction—both life and death, beauty and danger—it teaches us about nature’s extremes and our responsibility to protect them. For researchers, it’s a living lab. For adventurers, a surreal destination. For locals, a sacred land. And for all of us, a reminder of Earth’s incredible diversity.

| Topic | Detail |

|---|---|

| pH Level | Between 10 and 12, similar to household ammonia or bleach |

| Temperature | Often 40–60 °C in the summer, especially in shallow areas |

| Mineral Content | Rich in sodium carbonate and bicarbonate, sourced from nearby volcanic activity |

| Petrification Process | Birds and mammals that die in the lake dry out and calcify, appearing “mummified” |

| Flamingo Habitat | Supports 75% of the global population of lesser flamingos, which breed on isolated salt flats |

| Scientific Value | Studied by NASA and biologists for insights into extremophiles and astrobiology |

| Tribal Significance | Considered sacred and dangerous by the Maasai people |

| Conservation Status | Protected by Tanzania National Parks Authority; UNESCO monitoring development threats |

| Official Resource | Tanzania National Parks Authority |

What Makes Lake Natron So Dangerous?

Lake Natron owes its eerie properties to a combination of extreme alkalinity, volcanic influence, and high temperature. Its chemical makeup is largely due to runoff from Ol Doinyo Lengai, the only known active carbonatite volcano in the world. This volcano releases sodium carbonate and other minerals that pour into the lake basin, turning the water into an alkaline cocktail.

Extreme Alkalinity

The lake’s pH ranges from 10 to 12, making it one of the most alkaline bodies of water on Earth. To put that in perspective, a pH of 7 is neutral (like pure water). Anything above 9 can cause chemical burns, and Lake Natron is well past that.

The high alkalinity is caused by a mix of volcanic ash and sodium carbonate. These chemicals were once used in Egyptian mummification, which is ironically appropriate, considering what happens to the lake’s unfortunate victims.

Scorching Temperatures

During the dry season, temperatures can soar to over 60 degrees Celsius (140°F) in the shallow parts of the lake. This evaporates the water quickly and concentrates the minerals, intensifying the chemical environment.

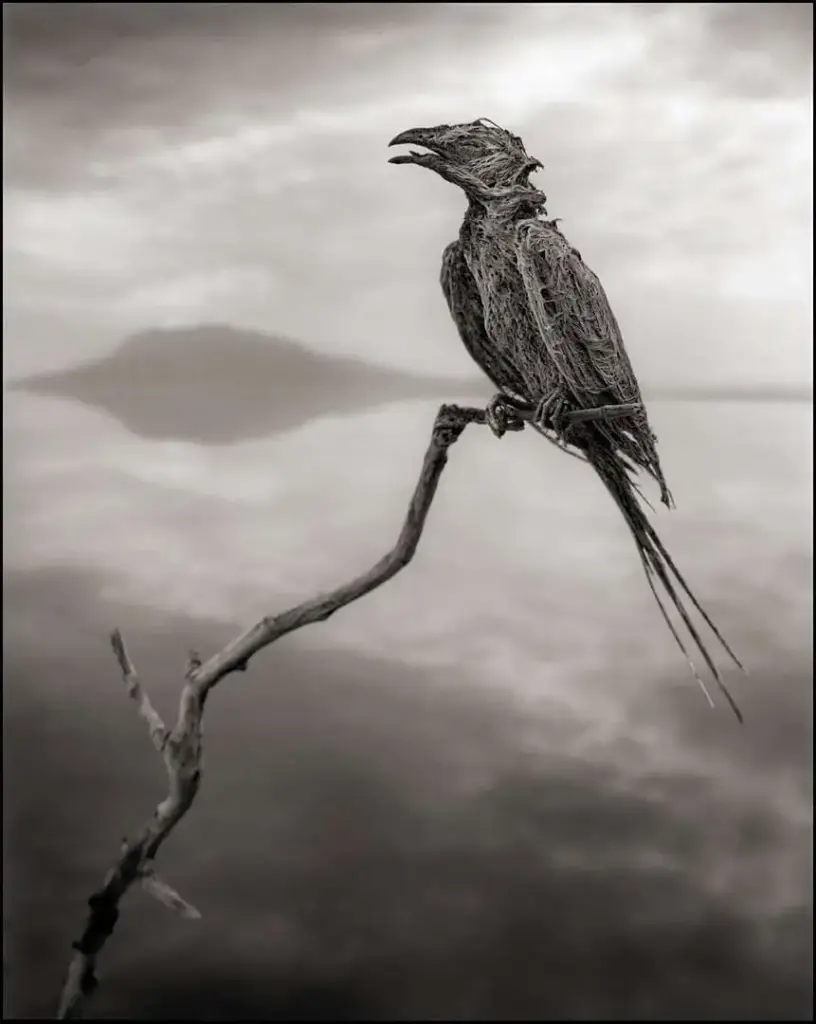

The “Petrification” of Animals

Despite how it looks, the animals that appear to be “turned to stone” aren’t turned into actual rock. Instead, the combination of heat, dehydration, and mineral coating causes a form of natural mummification.

Here’s what typically happens:

- A bird or bat flies over the lake and mistakes the glassy surface for open water.

- It crashes into the highly caustic water and dies from burns or drowning.

- The body is preserved by rapid dehydration and chemical coating.

- Over time, sodium carbonate binds to the skin and feathers, giving it a stony appearance.

Photographer Nick Brandt famously documented these preserved animals in his haunting series The Calcified. He positioned the remains in lifelike poses, emphasizing their tragic beauty and bringing international attention to this unique lake.

Nature’s Petrifying Secret: How Life Survives in Such Harsh Conditions

Although the lake seems like a death zone, some life forms actually thrive here—mainly due to millions of years of evolutionary adaptation.

Lesser Flamingos

Lake Natron is the primary breeding ground for 75% of the world’s lesser flamingos. These birds feed on cyanobacteria that flourish in the salty water. The flamingos build nests on isolated salt islands, safe from predators thanks to the lake’s hostile chemistry.

Flamingos are well-equipped to deal with the salt and alkalinity. Their tough legs and specialized glands allow them to excrete excess salt, and their long necks let them feed while standing in shallow water.

Microorganisms and Algae

Lake Natron is home to halophiles (salt-loving organisms) and alkaliphiles (alkaline-tolerant bacteria). These include species of Spirulina algae, which provide the main food source for flamingos.

These microbes produce vibrant colors—from reds to oranges—turning parts of the lake into a painter’s palette from above. In satellite images, Natron appears red, pink, or deep orange depending on the water’s concentration.

Tribal Lore and Cultural Significance

To the Maasai people, Lake Natron is not just a lake—it’s sacred ground. Known in the Maasai language as “En-kare Naitore” (terrifying water), the lake features in many tribal legends.

Some stories speak of spirits that guard the lake, punishing those who venture too close. Others tell of animals disappearing into its surface, never to return. For generations, these oral histories described exactly what scientists now observe with calcified remains.

The lake’s spiritual status means locals typically avoid using its water or fishing in it, inadvertently contributing to its preservation.

Scientific Research and Global Importance

Lake Natron is a goldmine for scientists studying extremophiles, ecosystem resilience, and even potential life on other planets.

Astrobiology and NASA

Because of its resemblance to ancient Martian lake beds, Lake Natron has been used by NASA and astrobiologists as a model environment. Studying how organisms survive in such extremes helps researchers develop hypotheses about where life could exist elsewhere in the universe.

Environmental Monitoring

Changes in the lake’s water level or chemistry provide early warnings about climate change and volcanic activity. Because it is so sensitive to environmental shifts, Lake Natron acts like a “canary in the coal mine” for East Africa’s Rift Valley system.

Threats to the Lake’s Future

Despite its protected status, Lake Natron faces real dangers from industrial development and human interference.

Soda-Ash Mining

In the early 2000s, proposals to mine soda ash from the lake were met with strong opposition from conservation groups. Extracting these minerals could alter the lake’s chemical makeup, threatening the flamingo breeding grounds and killing off microbial life.

Hydroelectric Development

Plans for dams and hydroelectric stations along rivers feeding the lake could reduce freshwater inflow. This would increase salinity levels, disrupt microbial balance, and potentially drive flamingos away.

Tourism Mismanagement

While eco-tourism can help fund conservation, unmanaged tourism brings litter, pollution, and disturbance to sensitive areas. Off-road vehicles and illegal drone photography are rising concerns among park rangers.

How to Visit Lake Natron Responsibly?

If you’re planning to see this natural marvel for yourself, you must plan carefully and travel respectfully.

Best Time to Visit:

Dry season: June to October or January to March, when flamingo nesting is at its peak.

Where to Stay:

Eco-lodges near the lake offer guided tours and contribute to local economies. Lodges like Lake Natron Camp offer solar power, composting toilets, and local employment.

What to Bring:

- Wide-brim hat and breathable clothing

- Sunscreen and refillable water bottle

- A quality camera (but no drones unless permitted)

- Reusable bags—no single-use plastics

What to Avoid:

- Don’t take rocks or “statues” as souvenirs

- Don’t feed or chase wildlife

- Don’t wander off trails—much of the lake’s bed is unstable and corrosive

This Shocking New Theory of Life Doesn’t Involve Monkeys or Dolphins—And It’s Blowing Minds

Neither Glitch Nor Myth: The Strange Case of Vostok Island’s Disappearance on Google Maps

Not Gold, Not Platinum—This Man’s Mysterious Rock Was Worth More Than Both and Came from Space

A Practical Field Guide for Visitors and Researchers

- Get Permits through the Tanzania National Parks Authority.

- Hire a local guide—not just for safety, but to respect local knowledge.

- Visit early mornings for the best lighting and cooler temperatures.

- Join conservation talks hosted at eco-camps and ranger stations.

- Support local artisans by buying crafts instead of mass-produced trinkets.