Egyptians Used Iron From Space in Sacred Objects: Not gold. Not copper. The real treasure of ancient Egypt came from the sky. For centuries, people thought the earliest iron tools found in Egyptian tombs were simply early smelting attempts or trade items. But new research has confirmed what ancient Egyptians likely knew thousands of years ago: the iron used in their most sacred objects wasn’t mined—it fell from the sky.

That’s right. Before humans learned to extract iron from the earth, the metal they used came from meteorites—iron-rich space rocks that crashed into Earth. Ancient Egyptians called it “iron of the sky”, and they turned it into powerful symbols of royalty, divinity, and cosmic connection. Let’s dive into how meteoritic iron became part of one of the world’s greatest civilizations—and why it still matters today.

Egyptians Used Iron From Space in Sacred Objects

Long before furnaces blazed and forges roared, ancient Egyptians shaped metal from the stars. Their meteoritic iron beads and daggers weren’t just tools—they were symbols of power, spirit, and cosmic identity. From the Gerzeh beads to King Tutankhamun’s blade, these sacred objects remind us that early humans didn’t just survive—they reached for the heavens, touched what fell, and made it their own. Today, we look back in awe—not just at what they made, but how they understood it. Not gold. Not copper. But iron from the sky.

| Highlight | Details | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Tutankhamun’s dagger | 34 cm blade, ~10.8% nickel, 0.58% cobalt—clear meteoritic signature | Meteoritics & Planetary Science |

| Gerzeh beads (~3300 BCE) | Oldest known iron artifacts, hammered from meteorite fragments | UCL & Petrie Museum |

| Ancient term | “Bi-A-n-pt” in hieroglyphs, meaning “iron from the sky” | Pyramid Texts & hieroglyphic studies |

| Meteorite crater | Kamil Crater in Egypt: source of iron meteorite fragments | Egyptian Geological Museum |

| Wider use | Meteoric iron used in Mesopotamia, China, Syria, Europe, Greenland | Archaeological survey studies |

| Smelting timeline | Large-scale iron smelting in Egypt began ~700 BCE | Archaeometallurgical records |

Why Egyptians Used Iron From Space in Sacred Objects Matters?

Iron changed history. But before people could smelt it, meteoritic iron was the only iron available to ancient civilizations. It was rare, tough, and clearly not of this world. For Egyptians, who viewed the heavens as the source of divine power, this space metal became a sacred material.

Before the Iron Age, meteoritic iron was so rare it was used almost exclusively in:

- Royal artifacts

- Religious tools

- Amulets and spiritual symbols

- Ceremonial blades

Because it came from above—literally the sky—Egyptians associated meteoritic iron with gods, stars, and the afterlife. When they shaped it, they weren’t just crafting tools. They were handling the universe itself.

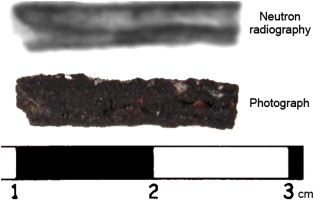

1. The Gerzeh Beads: Iron from 5,300 Years Ago

The story of meteoritic iron in Egypt starts at the Gerzeh cemetery, about 70 kilometers south of Cairo. There, in a tomb dated around 3300 BCE, archaeologists discovered tiny iron tube-shaped beads alongside gold and semi-precious stones.

When British archaeologists found them in 1911, they didn’t realize how special they were. But in 2013, using advanced scanning technology, scientists from University College London (UCL) confirmed that the beads contained over 30% nickel—a sure sign of meteoritic origin.

The technique used to shape them was equally impressive. Ancient artisans:

- Cold-hammered the meteoritic iron into thin sheets

- Rolled the sheets into cylindrical beads

- Combined them with organic materials and gold

- Polished them to resemble high-value jewelry

These aren’t just trinkets. They represent some of the earliest ironworking in human history—and they were made without furnaces, forges, or smelting.

2. Tutankhamun’s Dagger: A King’s Blade from the Stars

Fast-forward nearly 2,000 years to Tutankhamun, the boy king of Egypt. When his tomb was discovered in 1922, one of the most eye-catching objects was a beautifully crafted iron dagger with a gold handle.

For decades, experts debated where the iron came from. Egypt wasn’t smelting iron at that time. So was it imported? Or… something else?

In 2016, a team of Italian and Egyptian scientists used X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to analyze the blade. The results were conclusive: it contained 10.8% nickel and 0.58% cobalt—identical to iron meteorites.

This dagger wasn’t a battlefield weapon. It was a symbol of divine rule, buried with a pharaoh to accompany him to the stars. The craftsmanship showed a high degree of sophistication: the blade had been forged, not just hammered, preserving the meteoritic structure while shaping it for ceremonial use.

3. “Iron of the Sky”: Language and Meaning

Egyptians didn’t just use this iron—they understood it came from above. In hieroglyphs dating from the 13th century BCE, the word used for iron was “bi-A-n-pt”, literally translated as “metal of heaven” or “iron from the sky.”

Even in religious texts like the Pyramid Texts (written before 2300 BCE), iron is mentioned in a cosmic context. Phrases such as “the king’s bones are iron and his limbs are stars” emphasize a belief in the connection between iron and the gods.

The mythological context is just as rich. Some scholars suggest that the famous benben stone in Heliopolis—considered a resting place of the sun god Ra—may have been a meteorite.

4. Egypt’s Own Meteorite Crater

The idea that Egyptians used local meteoritic iron gets even stronger with the discovery of Kamil Crater in Egypt’s New Valley Governorate. Found in 2008 via satellite imagery, the crater is estimated to be less than 5,000 years old. Thousands of pieces of meteoritic iron were scattered in the surrounding desert.

Many of those fragments are now housed in the Egyptian Geological Museum. Could some of that very iron have made it into beads or blades? It’s highly possible. The crater’s timeline fits perfectly with early meteoritic artifacts.

5. How Other Cultures Used Star Metal

Egypt wasn’t alone. Meteoric iron was treasured across the ancient world.

- Mesopotamia: Called meteoritic iron “sky metal” and used it for ceremonial tools.

- Syria and Anatolia: Kings were buried with iron daggers centuries before iron smelting began.

- China: Artifacts from around 1400 BCE show meteoritic iron used in blades and jewelry.

- Inuit of Greenland: Used meteoritic iron from the Cape York meteorite for tools before contact with Europeans.

- Namibia: The Nama people used the Gibeon meteorite for centuries as a metal resource.

In all these cases, the metal was considered rare, valuable, and powerful. Its origin—the stars—only enhanced its spiritual and cultural importance.

6. Techniques That Still Impress Experts

You’d think working with space metal would be a messy affair. But ancient smiths had it figured out:

- Cold working was used for delicate shaping.

- Annealing (gentle heating) helped control brittleness.

- Surface polishing brought out natural sheen.

- Some items even retained the Widmanstätten pattern, a crystal structure unique to meteorites.

Modern metallurgists note that these ancient techniques managed to retain both the shape and molecular structure of meteoritic iron—something that still takes care and experience today.

This Shocking New Theory of Life Doesn’t Involve Monkeys or Dolphins—And It’s Blowing Minds

Not Gold, Not Platinum—This Man’s Mysterious Rock Was Worth More Than Both and Came from Space

7. What This Means for Today’s Professionals

Whether you’re a conservator, jeweler, museum curator, or educator, this topic offers several actionable insights:

- Artifact identification: Test for nickel (10–30%) and cobalt (0.5–1%) content using portable XRF for field-ready verification.

- Preservation matters: Don’t overheat meteoritic artifacts—excessive heat destroys their cosmic crystal structure.

- Exhibit storytelling: Pair scientific facts with mythological context for richer museum displays.

- Ethical sourcing: Ensure meteoritic samples (modern or ancient) are legally acquired and preserved.

- Inspiration for design: Contemporary artisans can draw from ancient shapes to create jewelry, blades, or religious icons echoing cosmic themes.