3,000-Year-Old Arrowhead Made of Space Metal: Imagine holding a weapon older than the alphabet—crafted not just from any old metal, but from space metal. That’s not science fiction; it’s real. A 3,000-year-old arrowhead, forged from iron that came from a meteorite, was discovered in Switzerland, and it’s reshaping how we understand ancient civilizations. This remarkable find is proof that Bronze Age people were resourceful, curious, and surprisingly connected across long distances. The artifact wasn’t just a tool—it was a sign of status, spirituality, and early trade. And now, thanks to modern science, we’re learning more about its cosmic origin and the people who used it.

3,000-Year-Old Arrowhead Made of Space Metal

The 3,000-year-old arrowhead from Mörigen, Switzerland, is more than a museum artifact. It’s a storybook carved from the cosmos—telling us how ancient people reached for the stars and pulled pieces of them into their lives. From the labs of Bern to the crater fields of Estonia, and through the hands of Bronze Age artisans, this small tool speaks volumes. It tells us that the past isn’t lost—it’s still here, waiting to be understood. Whether you’re a scientist, a teacher, a student, or just someone who loves a good story, this discovery connects space, time, and humanity in one breathtaking artifact.

| Highlight | Details |

|---|---|

| Artifact Name | Mörigen Arrowhead |

| Estimated Age | ~3,000 years (circa 900–800 BCE) |

| Discovered | Mörigen, Switzerland (1873) |

| Material | Meteoritic iron (IAB type) |

| Composition | ~7.2% Nickel, 0.85% Cobalt, trace Germanium and Gallium |

| Confirmed Space Origin | Yes, from a meteorite |

| Likely Meteorite Source | Kaali Crater, Estonia |

| Analysis Methods | X-ray tomography, gamma spectrometry, muon-induced X-ray emission |

| Known Similar Artifacts | Approx. 56 worldwide |

| On Display | Bern Historical Museum, Switzerland |

| Exhibition | “And Then Came Bronze!” (Feb 1, 2024 – Apr 25, 2025) |

| Official Resource | Bern.com |

What Makes This Arrowhead So Special?

Most arrowheads from the Bronze Age were made of—well—bronze. The Iron Age hadn’t even begun yet, and people didn’t know how to smelt iron from ore. That’s why the use of meteoritic iron, which came crashing down from the sky in fireballs, was so extraordinary. It was rare, mysterious, and probably considered sacred.

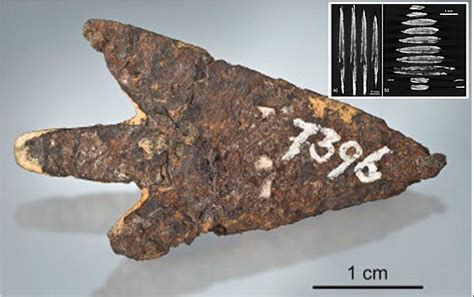

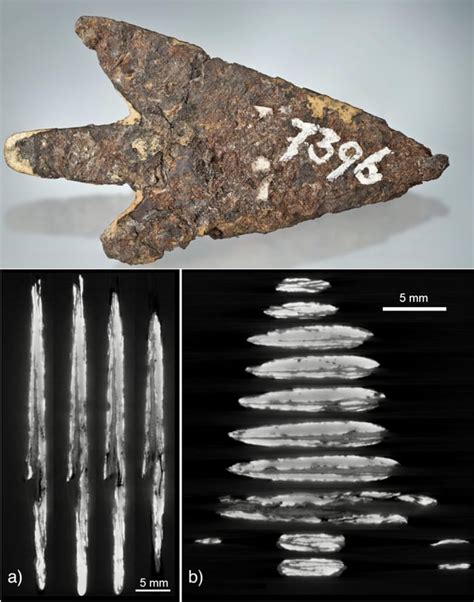

The Mörigen arrowhead is a small, leaf-shaped object measuring just over 3 centimeters. It was originally unearthed in the 19th century at a lakeside pile-dwelling settlement near Lake Biel in Switzerland. For years, its unusual composition was overlooked. But recent analysis using advanced, non-destructive techniques confirmed what researchers suspected—it was made from a meteorite.

How Scientists Know a 3,000-Year-Old Arrowhead Made of Space Metal?

The discovery would be meaningless without proof. That’s where science comes in.

Researchers from the Natural History Museum of Bern used three main techniques:

X-ray Tomography

This imaging technique allowed scientists to see the internal structure of the artifact without cutting into it. It revealed how the object was forged and showed signs of human workmanship like grinding and sharpening.

Gamma Spectrometry

By measuring the gamma rays emitted by the material, scientists could determine its unique elemental fingerprint, identifying high levels of nickel, cobalt, and trace elements like germanium and gallium—classic indicators of meteoritic iron.

Muon-Induced X-ray Emission (MIXE)

This cutting-edge method helped detect trace elements that wouldn’t show up in standard X-rays. It’s rarely used on ancient objects, but it was crucial for confirming the space-metal composition without damaging the artifact.

Together, these tests confirmed the arrowhead was made from IAB-type meteoritic iron, which forms when molten metal in a large space rock slowly cools and separates from the silicate part of the meteorite.

Not Swiss at All: It Likely Came from Estonia

At first, scientists thought the material might have come from the Twannberg meteorite, which fell only 8 kilometers from the site. But the arrowhead’s chemical signature didn’t match. It had too much nickel and cobalt.

Instead, the composition closely matched the Kaali meteorite, which landed in Estonia around 1500 BCE. That’s roughly 600 miles away. This suggests that meteoritic iron was traded across vast distances long before roads, maps, or modern tools.

This was not just a local wonder—it was international Bronze Age craftsmanship, centuries before the concept of “international” even existed.

What This Discovery Tells Us?

Ancient People Were More Connected Than We Thought

Just like Native American trade networks stretched from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast, Bronze Age Europeans were trading across massive distances. Materials like amber, tin, and now meteoritic iron made their way from one region to another, proving that early societies were not isolated.

Meteoritic Iron Was Considered Special

Because iron smelting wasn’t yet invented, the only way people could get iron was from meteorites. This made it rare and highly valuable—likely reserved for special individuals or spiritual purposes. The Mörigen arrowhead was likely not used for warfare or hunting, but for ceremony or prestige.

Early Metallurgy Was Surprisingly Sophisticated

The arrowhead shows signs of expert craftsmanship. People knew how to heat, shape, and sharpen this tough metal. The presence of tar residue on the base suggests it was once hafted onto a shaft, likely for display or ritual use.

A Cultural Parallel: Native American Sacred Materials

Indigenous cultures in North America, such as the Hopi, Anishinaabe, and Lakota, have long histories of using sacred stones and metals. Items like obsidian, turquoise, and copper were treated not just as tools or ornaments—but as gifts from the Earth and sky.

In similar fashion, meteoritic iron in the Bronze Age was probably seen as sky metal—a gift from the gods or ancestors. Such materials often carried spiritual significance and were used in rites, burials, or as symbols of power.

This connection helps us understand how different ancient societies—despite being thousands of miles apart—shared similar beliefs about the natural world.

What This Means for Museums and Educators?

If you’re in education or museum curation, this discovery offers an opportunity to engage both young students and lifelong learners with a compelling blend of archaeology, science, and cultural storytelling.

Ideas for Classroom Use:

- Build a cross-disciplinary lesson connecting science (space and metals) with history (Bronze Age Europe).

- Use comparative anthropology to show how other cultures used rare or spiritual materials.

- Create hands-on activities like 3D printing arrowhead replicas or mapping ancient trade routes.

For Museums:

- Exhibit pieces should feature both scientific data and cultural interpretation.

- Include interactive tools to let visitors “test” materials as ancient scientists would.

- Connect this story with other cosmic artifacts, like Tutankhamun’s iron dagger.

Guide for Metal Detectorists and Amateur Historians

If you’re out exploring and think you’ve found something rare, here’s what to do:

1. Test for Magnetism: Meteoritic iron is magnetic.

2. Look for Fusion Crust: A thin, dark outer layer from atmospheric entry.

3. Check for High Nickel Content: Only lab testing can confirm this.

4. Document Everything: Take detailed notes on where, when, and how you found it.

5. Contact Local Experts: Museums or universities often have archaeometallurgists who can help verify your find.

Warning: Many countries have strict laws about discovering and reporting artifacts. Always do your homework first.

Not Gold, Not Copper—Egyptians Used Iron From Space in Sacred Objects, New Study Reveals

Not Gold, Not Platinum—This Man’s Mysterious Rock Was Worth More Than Both and Came from Space

Starlink in Trouble? Solar Storms Disrupt Elon Musk’s Satellite Network